We’re often asked the question, “What does a ‘typical day’ in the life of Long Miles Coffee look like?”

The truth? It depends on when you ask. Although coffee harvest only happens once a year in Burundi and usually lasts around three months (sometimes more), growing and producing coffee is a year-round effort. On any given day of the week, the Long Miles team could be spread out between the country’s capital, or upcountry at our washing stations where coffee is grown. For the thousands of smallholder coffee farmers that we work with, a “typical day” is completely different from our own. The time that coffee farmers in Burundi spend on farming activities is divided between a multitude of crops, not just focused on coffee.

Here’s a glimpse at what an “average” year in the life of Long Miles Coffee in Burundi looks like:

JANUARY-FEBRUARY

It’s the beginning of the year. The country is experiencing “impeshi”, which translated from Kirundi (the local language spoken in Burundi) means “small dry season”. Depending on the area and soil structure, farmers are planting a variety of crops in this season, especially beans, potatoes, and peas. If coffee farmers have access to insecticides, they will be spraying them on their coffee trees as well as weeding their coffee farms. Some will even start pruning their coffee trees.

January is usually the time that our head of Production and Quality Control, Seth Nduwayo, leads our annual Coffee Quality and Production Training. It’s also the time when we start preparing the annual calendar for our social and environmental impact projects: PIP (Integrated Farm Plan), Farmer Field School, Trees For Kibira, and Womxn and Youth Empowerment Programs.

The Story team, lead by Joy Mavugo, is out in the coffee hills, connecting with coffee farmers to hear their thoughts in the weeks that prelude coffee harvest. Most importantly, this is when we start applying for our annual production license- something that coffee producers in Burundi must do at the start of each year. Without it, we wouldn’t be able to open our washing stations for cherry collection or begin processing the first coffees of the season.

Every week, the Long Miles Coffee Scouts are visiting each of the hills that we collect coffee from, checking on the health of our own coffee farms, meeting with Farmer Field School team members and teaching best agricultural practices, making note of the visible effects of climate change in the coffee hills, keeping a record of the number of antestia caught, distributing and planting seedlings from our Trees For Kibira nurseries. To diversify our coffee farms, our team at Heza Washing Station is maintaining the handbuilt cowsheds and laying down new fodder for our two mama cows and their calves.

Together with our washing station managers and production teams, the Coffee Scout leaders are also holding meetings with community development officers and partner coffee farmers, hearing from them if there were any challenges or issues during the previous coffee harvest and discussing ways to resolve this before the upcoming coffee harvest.

MARCH-JUNE

The country is experiencing its biggest rainy season of the year. The coffee cherries are red, ripening, and ready to be picked. The antestia bug (the insect thought to be linked to the Potato Taste Defect) thrives during this time because the cherries are soft and sweet, making it easier for the bug to bore holes into the cherry skins. Farmers are scouting for these bugs in their coffee trees and if they find them, are removing them by hand.

The end of March usually marks the opening of coffee harvest in Burundi, and coffee farmers will spend most of their days hand-picking cherries then walking to deliver them to the nearest washing station or collection point. Generally, other crops aren’t planted in this season because coffee is on everyone’s mind.

April and May roll around, and coffee harvest is in full swing. It’s one of the busiest times of year for our team. The Coffee Scouts spend their days between guiding coffee farmers through selective cherry picking on their farms and at the washing stations or collection points, assisting with farmer reception and cherry quality control. Our team also works alongside our partner coffee farmers, harvesting cherries from the Long Miles Coffee Farms. Each delivery of cherry is processed, either as a fully washed, natural, or honey-processed coffees, and left to dry on raised drying tables.

The Story team spends these weeks following our team’s activities, connecting with coffee farmers on their farms, and documenting their harvest, or at the washing stations following the production of coffee.

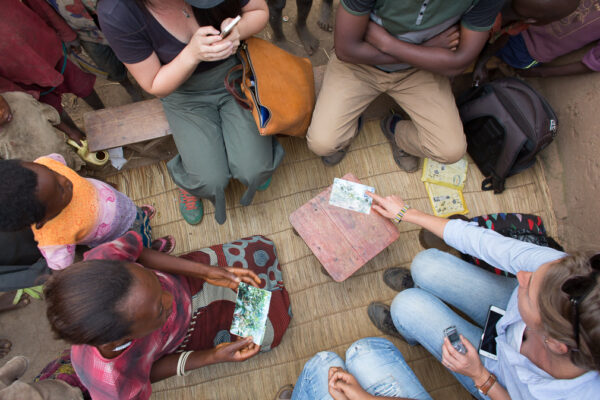

This is usually the time that we get to welcome our roasting partners in Burundi to experience a slice of coffee harvest, see coffee in production, connect with our team and partner coffee farmers, and join us around the cupping table to taste a selection of fresh crop coffees.

JULY-AUGUST

The start of July usually signals that coffee harvest is coming to a close in Burundi. Most of the parchment coffee is either off the tables or about to come off. Our washing stations no longer receive coffee cherries, and our team’s focus shifts to the dry mill.

Our Production and Quality team at the dry mill is focused on constructing micro-lots and preparing coffees for export. They are regularly sending samples to our Long Miles Coffee lab, where hundreds of cups of coffee are cupped, analysed, and scored by our team before being sent as samples to our roasting partners the world over. This work starts in July and continues until the end of the year.

The country-wide coffee pruning campaign officially opens, and the Coffee Scouts are helping coffee farmers to identify which coffee trees should be pruned or stumped. All around farm maintenance is happening at the same time: weeding, applying organic fertilizers, and mulching the ground to keep it moist during the upcoming dry season.

At the helm of our Social and Environmental Impact Leader, Epa Ndikumana, the Coffee Scouts are also collecting samples of soil for testing, and analysing the benefits of intercropping banana trees with coffee on our coffee farms. Our Story team is there to capture it all: the dry mill, the post-harvest activities, and most importantly, farmer payments.

Farmer Payday is the one day of the year when all of the coffee farming communities that we work with receive payment for the coffee cherries that they delivered to us during harvest season. The money that most farmers earn from growing coffee is spent on their children’s school tuition and supplies, home repairs, and investing in other income-earning projects. In the weeks leading up to payday, our team works hard behind the scenes, counting money and preparing each farmer’s payment. Hill by hill, each farmer that we work with is paid for every kilogram of coffee cherry that they delivered to a Long Miles Washing Station or collection point.

SEPTEMBER-DECEMBER

The country is experiencing “agatas”, which translated from Kirundi means “small rainy season”. These are the months that are considered the main planting season in Burundi. Whatever farmers choose to grow is planted at this time.

The mature coffee trees start to flower- depending on the amount of rainfall in the country- and the coffee cherries are in the early stages of developing. This is the time for coffee farmers to be maintaining their coffee nurseries, planting new coffee trees, and weeding their plantations. Those who have access to lime and fertilizer will start applying it on their coffee farms.

The coffees at the dry mill continue to be milled, bagged, and processed before being loaded onto trucks and headed to our roasting partners across the world.

Meanwhile, the Coffee Scouts are evaluating the growth and survival rate of the Trees For Kibira seedlings in the nurseries. As the year comes to a close, a bonus payment is made to the coffee farmers who delivered high quality cherries throughout the season.

There’s no short way of answering the question, “What does a ‘typical day’ look like for you?” No matter the year, there’s no small amount of words to share with you what producing coffee in Burundi looks like for our team. As we write this, the coffee cherries have already started to ripen, rain has fallen, and our team has started preparing for the upcoming harvest season. We can’t wait to share what this year holds with you!