“To have a washing station at Ninga is like a country that fought for independence, and got it. I will always celebrate this victory. No one will take it from us.”

We have been thinking about building a coffee washing station on Ninga hill for years. It’s been on our minds ever since we opened the doors of Bukeye, the first washing station that we built, for our inaugural coffee harvest in Burundi. We wrote about this not so long ago. Looking back, it has taken us close to seven years to make Ninga Washing Station happen.

Ninga hill is seated in the Butaganzwa Commune, an incredibly competitive and politically-charged area to work in. During those early years of producing coffee, we found that coffee farmers from Ninga and its surrounding sub-hills were streaming into our Bukeye Washing Station, walking more than fifteen kilometres (a journey that can take up to three hours by foot) to deliver their cherries. After speaking with some of these farmers and visiting their coffee farms, our team soon realized that they were producing quality coffee but didn’t want to deliver their cherries to other nearby washing stations because they felt like they couldn’t trust them with their coffee. Corruption, unbalanced scales, mistreatment of the coffee farming community, and delayed payments for coffee delivery broke farmers’ trust with other washing stations that over-promised and under-delivered.

“Times are not the same. I still remember when I was imprisoned because I refused to stop delivering my own coffee at Bukeye Washing Station. There was a strong hope of having a washing station at home. One night, during that time, I sat in my house thinking about the future of my coffee, but I couldn’t see it.”

– Tharcisse from Ninga hill in Burundi.

Hearing a similar, disheartening account from people on Ninga hill over and over again, it was clear to our team that something needed to change.

2017

That opportunity presented itself to us near the end of 2017, when we were able to buy a piece of land seated at 1900masl on Ninga hill that was flanked by the Nkokoma River.

2018

We applied to the National Coffee Board at the beginning of the year for authorization to start construction of the washing station. It took ten months for the board to set up a “technical commission” to check that the land had everything it needed. Does it really belong to Long Miles? Check. Is there a fair distance between where our washing station will go and other washing stations in the area? Check. Would coffee farmers in the area find it valuable to have another washing station here? Check. Would processing coffee here have any negative implications on the environment? Check. Will the washing station’s activities be profitable? Check.

2019

In October, more than a year after the technical commission had been set up, we were finally able to sign off all of the necessary paperwork and got permission to start the build of Ninga Washing Station. However, the country’s coffee sector was going through major shifts at the time. The restructuring of Burundi’s National Coffee Board coupled with rumblings of the government nationalizing the coffee sector caused a number of delays for the start of construction, and a landslide of uncertainty for coffee producers in the country.

2020

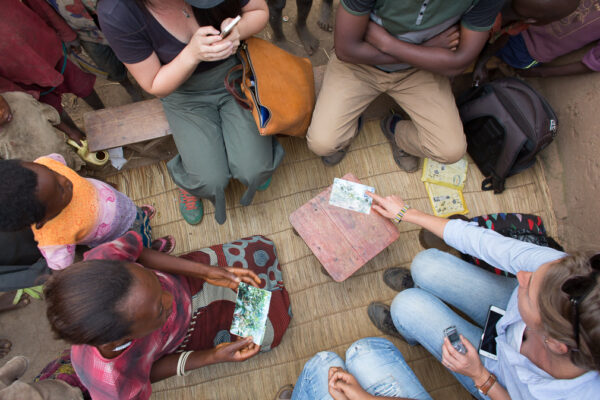

The new National Coffee Board was in place, and the rumours of nationalizing Burundi’s coffee sector were at bay. With harvest opening early April, forty-five newly built drying tables, and our McKinnon yet to be installed, we decided to start producing our first natural processed micro-lots of the season- the only coffees to be processed at Ninga Washing Station that year. By the end of August, we held the first farmer payday day at our official Ninga Washing Station site and celebrated alongside our partnering coffee farmers.

“For five years, I’ve didn’t participate in payday because it was far from home. I used to pay someone to go and collect my money on payday. I was so happy to meet with other people from around the entire hill and even saw a friend that I hadn’t seen in twenty years! I thought that she might have died because so many from our generation have. It was a great day.”

– Matilda, a seventy-five year-old old coffee farmer from Ninga hill.

What does building Ninga Washing Station mean for the future of coffee on Ninga hill?

“Having a washing station in our area is a big development, not only for coffee farmers but for everyone in our community.”

During the construction of the washing station, 200 hundred people were employed representing almost the same numbers of households from the community. We’ve been encouraged to hear that the washing station will bring change for those growing coffee in the area too.

“What is important is that we now have a washing station at home. Things at the washing station are organized, the farmer card system is fair, and the scales are good. You’re not stealing our coffee. This is encouraging.”

– Leonard, coffee farmer from Gikungere, close to Ninga hill.

Many farmers from Ninga hill won’t have to walk as far to deliver their cherries, which will help to shorten the time between coffee being picked and coffee being pulped at our washing station. This shortened time helps to reduce the risk of enzymatic reactions taking place within the coffee cherries that could impart unwanted flavour to the finished cup of coffee, and allows for the greatest potential of consistency going into pulping.

“I thought about stopping to grow coffee, but glory to God, the hope that was in me did not accept defeat! This is a victory. It is a miracle! I helped to build the washing station, and am now working as a guard. I have a story to tell to my grandchildren. Ninga Washing Station is bringing a new beginning of growing coffee. In my mind, I am like a new coffee farmer. It is amazing.”

– Tharcisse from Ninga hill in Burundi.

With our newly fitted McKinnon and the final touches happening at the washing station, we’re looking forward to producing fully washed and natural process coffees this season. We’ll also be experimenting with anaerobic lots, so keep your eyes peeled for our updates when coffee harvest opens in Burundi next month!